The French Revolution, a period of radical political and societal transformation in France that spanned a decade from 1789 to 1799, indelibly shaped the trajectory of modern history. This seismic event, beginning with the financial crisis of the Bourbon monarchy and ending with Napoleon Bonaparte's coup of 18 Brumaire, was driven by socio-economic inequities, Enlightenment ideas, and widespread famine.

Its profound legacy has been a continuous source of study and interpretation, serving as a critical touchstone for discussions on liberty, equality, and fraternity — the fundamental principles that still inform democratic ideals today, not to mention the French Revolution fostered the rise of a middle-class society.

Because of all this, studying the French Revolution has become pretty standard in history classes of all levels, from high school to post-graduate courses. Almost every college in the United States offers a course on the French Revolution of 1789 and AP classes like AP European History covers this topic for high school students. Since so many students will be exposed to and learn about the French Revolution, we at BrokeScholar decided to assemble the most comprehensive outline and timeline of the French Revolution, including dates, events, and overall key terms and concepts, to help you easily master this subject.

Let us begin.

Table of Contents

I. Pre-French Revolution Timeline: 1589-1789

You can’t truly understand the great French Revolution that broke out in 1789 without knowing the history of the so-called Ancien Regime (the “Old Regime”) — the reigning political and social system of pre-revolutionary France. There’s no precise date for the beginning of the Ancien Regime but using the rise of the Bourbon dynasty as rulers of France — in the year 1589 — is a helpful starting point.

1589-1648: From the First Bourbon King to the Fronde

The years 1589 to 1648 witnessed significant changes in French history, marking the reign of the first Bourbon king, Henry IV, and culminating in a series of civil wars known as the Fronde. This epoch, just before the zenith of the French monarchy under Louis XIV, was rife with political strife, religious tension, and shifting social dynamics. Navigating the complexities of this era provides a richer understanding of the subsequent ascendancy of the absolute monarchy, and sets the stage for the societal transformations that would eventually culminate in the French Revolution.

[Portrait of King Henry IV of France, by Frans Pourbus the Younger. Henry IV is said to have coined the phrase, "A chicken in every pot, every Sunday”]

1589-1610: Reign of Henry IV

The period from 1589 to 1610 was marked by the reign of Henry IV, the first Bourbon king of France, whose tenure was instrumental in transitioning the country from the destructive Wars of Religion towards stability and relative prosperity. Ascending to the throne amid intense religious conflict, Henry IV, initially a Protestant, famously converted to Catholicism to appease his largely Catholic subjects, epitomized in the phrase "Paris is worth a mass." His reign was characterized by pragmatic political decisions, tolerance, and a focus on economic recovery. The Edict of Nantes, granting religious freedoms to Protestants and effectively ending the Wars of Religion, stands out as one of his most notable accomplishments. Additionally, Henry IV’s economic policies, implemented by his able minister, the Duke of Sully, laid the groundwork for a flourishing economy, while infrastructural developments modernized Paris.

August 1, 1589: King Henry III of France (of the House of Valois dynasty) is assassinated by fanatical Dominican friar Jacques Clément. Henry III and the entire kingdom is engulfed in the brutal, lengthy French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) fought mainly by the Catholic League and its Catholic supporters versus the Huguenots (French Protestants, who follow the Calvinist or Reformed church). Henry III was the last king of the Valois dynasty.

August 2, 1589: The Huguenot Henry of Navarre, a distant relative but the heir-presumptive by French Salic law, technically accedes to the French throne as Henry IV — the first king of the House of Bourbon. However, his opponents like the Catholic League and the Duke of Guise do not recognize him.

February 27, 1594: The coronation of Henry IV as King of France takes place at Chartres Cathedral after he abjures Protestantism and converts to Catholicism, not to mention defeated all of his opponents in war. This marks the true start of Bourbon monarchy (although he technically became king in 1589, his Catholic opponents in the French Wars of Religion didn’t recognize him) — the dynasty would last until 1789.

April 1598: The Edict of Nantes is pronounced by Henry IV, putting an end to the Wars of Religion and granting French Protestants religious, political, and civil rights in certain areas of the kingdom. It is an edict of limited toleration and does not recognize Protestantism in France as an official, legitimate religion. Still, it is a seminal step forward that would, unfortunately, be taken back almost 100 years later with the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685.

September 27, 1601: Birth of Louis XIII

May 14, 1610: Assassination of Henry IV by François Ravaillac, a Catholic zealot who stabbed him in the Rue de la Ferronnerie. His son succeeds to the throne as Louis XIII. The reign of King Louis XIII sees an increasing push toward absolutism, especially during Cardinal Richelieu’s tenure in office until 1642.

1610-1648: Reign of Louis XIII and Regency

The reign of Louis XIII, stretching from 1610 to 1643, and the Regency for his young son Louis XIV, lasted until he reached majority in 1651, but this period is punctuated by the outbreak of the Fronde in 1648, marking a transformative period in French history that set the stage for the absolute monarchy of "the Sun King", Louis XIV. This era was dominated by significant political figures such as Cardinal Richelieu and Cardinal Mazarin, whose influential policies significantly enhanced royal authority at the expense of the nobility. Their tenures marked the dawn of a stronger, centralised French state, although they were not without their detractors and resulted in considerable societal unrest.

[A portrait of King Louis XIII, second monarch of the Bourbon dynasty and the reigning king in Alexandre Dumas's The Three Musketeers]

May 16, 1610: Proclamation of the regency of Marie de Medici, the wife of Henry IV.

October 17, 1610: Coronation of Louis XIII at Reims Cathedral.

October 27, 1614-February 23, 1615: Last convocation of the Estates-General — the national meeting of the three estates of the realm — until it was called to meet for the first time in almost 200 years in 1789.

November 25, 1615: Louis XIII marries Anne of Austria in Bordeaux.

December 2, 1626-February 24, 1627: Last convocation of the Assembly of Notables until it was convened for the first time — in roughly 160 years — in 1787.

December 25, 1620: The Huguenots meet in La Rochelle. During this Huguenot general assembly in La Rochelle, the decision was taken to resist the royal threats to them by force and for Huguenots to establish a “State within a State”. This marks the beginning of a series of Huguenot rebellions, lasting from 1620 to 1629.

June 28, 1629: The The peace of Alès is an edict promulgated by the king of France Louis XIII after the siege of Ales. The signing of the edict comes after the surrender of La Rochelle, the last Protestant safe haven in France, after a siege of more than a year which ended in 1628, as well as after the sieges of Privas in May 1629 and Alès the following month, which put an end to the attempts at rebellion in the lower Vivarais. The Huguenot rebellions are brought to an end.

May 14, 1643: Death of Louis XIII and succession of the very young Louis XIV, the eventual “Sun King” and embodiment of absolutism. The 4-year-old Louis XIV is officially king, but his mother — Anne of Austria — serves as regent during his minority.

1648-1715: Absolutism and the Reign of Louis XIV, the “Sun King”

History professors have various dates delimiting the the Age of Absolutism, but generally seem to settle on roughly 1600 to 1789. This general timeframe works for a number of countries and their histories, such as:

- The attempts by the Stuart kings of England to rule as absolutist monarchs from 1603 — with the accession of James I to the throne — to 1642 and the outbreak of the English Civil War, pitting Parliamentarians against the absolutist Charles I.

- The reign of Tsar Peter the Great, who greatly strengthened the tsarist government's powers and military while at the same time "taming" his nobility by codifying their levels of status and all status groups of society in his Table of Ranks of 1722.

- The Enlightened absolutism of Frederick the Great of Prussia, who had soaked in the lessons of Prussia's history during the tumultuous Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) and understood the necessity of a well-ordered, well-armed state with a powerful central government to counter and eventually integrate the nobility into his absolutist system via the mechanism of being committed officers in the Prussian Army.

And the timeframe, of course, works for the Kingdom of France, with the growth of absolutism occurring most precipitously under the Bourbon dynasty — the dynasty that had emerged from the vicious religious and aristocratic civil conflicts of the Wars of Religion and the same dynasty that was nearly brought to the brink by noble revolt in the form of the Fronde, when both the Nobles of the Robe (noblesse de robe) — e.g. members of the Parlements — and the Nobles of the Sword (noblesse d'épée) — e.g. the discontented princes and nobles like Gaston, Duke of Orleans; Louis II, Prince de Condé; and his brother, Armand, Prince of Conti — rose up against the king's government.

1648-1653: The Fronde

The Fronde, a series of civil wars that convulsed France from 1648 to 1653, represents a critical juncture in French history, characterized by widespread opposition against the growing centralization of royal power. Triggered by the regency government's attempt to levy high taxes in the face of economic hardship, the Fronde was not merely a rebellion led by high-ranking nobles, but a complex socio-political movement that involved multiple factions, from the Parisian parlement and provincial nobility to urban commoners. This period encapsulates a nation in turmoil, struggling with the contradictions of its feudal past and a future trending towards absolutism.

[A battle between royalist and Frondeur forces in the Paris suburb of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, July 2, 1652]

May 13, 1648: Beginning in January 1648, the regent and Cardinal Mazarin have been trying to push through the enactment of 7 financial edicts, which customarily must be registered by the Parlement of Paris (the parlements being high courts of appeal as opposed to legislative bodies like the English parliament) in order to be legal and legitimate. These edicts include a tax to be levied on judicial officers of the Parlement of Paris. Not only did the Parlement refuse but on May 13, 1648, the four sovereign courts of France — the Parlement, Chamber of Accounts, Court of Aids, and Grand Council — all unite to condemn the edicts, as well as previous ones, and demand the royal government accede to constitutional reforms crafted by a committee of the four courts. This is the beginning of the Fronde — the greatest challenge to the power of the Bourbon monarchy and political system until 1789, when the French Revolution threw down a new challenge.

October 21, 1652-July 20, 1653: The Fronde is brought to an end by a victorious royal government. Louis XIV triumphantly enters Paris on October 21, 1652, moving into the Louvre (a palace at the time, not a museum like today). The signing of peace at Pézenas on July 20, 1653 by the rebellious Prince of Conti. This treaty definitively ends the Fronde of the princes.

1653-1685: Louis XIV Ascendant

The period of 1653 to 1685 marks the ascension and consolidation of power by Louis XIV, "the Sun King", defining an epoch of French history renowned for absolutist rule, cultural flourishing, and territorial expansion. Following the chaos of the Fronde, Louis XIV's reign began in earnest as he took the reins of governance into his own hands, determined to prevent the return of such widespread revolt. This era witnessed the king's centralization of power, the reduction of the nobility's influence, and the expansion of royal authority through his famous mantra, "L'État, c'est moi" ("I am the state"). Emblematic of his reign was the construction of the opulent Palace of Versailles, serving both as a symbol of France's grandeur and a strategic means to control the nobility. This period also saw France emerge as a dominant force in Europe, guided by the diplomatic maneuverings of his able minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert.

[Louis XIV, King of France, modello by Hyacinthe Rigaud, dated 1701]

March 9, 1661: Death of Cardinal Mazarin and the beginning of Louis XIV’s personal rule and control over the reins of government. He no longer will employ a chief minister like Richelieu or Mazarin for the rest of his reign.

May 24, 1667-May 2, 1668: War of Devolution is the first of Louis XIV’s many wars he would wage as king, with the goal of aggrandizing France and — since he identified himself personally with the state (“I am the state!”) — aggrandizing his own honor and prestige. The war is fought mainly between France and Spain in the Spanish Netherlands (modern-day Belgium), Franche-Comte (an old province that’s now part of the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté administrative region), and northern Catalonia in Spain.

April 6, 1672-September 17, 1678: The Franco-Dutch War was waged initially between France and the Dutch Republic before other European power eventually joined in the conflict, sometimes fighting for one side for a bit before jumping to the other. Although Louis XIV’s grand strategic objectives of destroying the Dutch Republic and conquering the Spanish Netherlands were not attained, he still managed to have most of his conquests confirmed in the Peace of Nijmegen.

May 6, 1682: Louis XIV officially establishes the French royal court at the Palace of Versailles, moving it from where it traditionally was in Paris.

October 26, 1683-August 15, 1684: The War of the Reunions was fought between France on one side and Spain and the Holy Roman Empire on the other. Louis XIV continued his push for greater territorial acquisitions and achieved much, but this war would serve as his highwater mark militarily. All of Louis XIV’s wars of aggression, taken together, had now seriously alienated the other European powers and generated the formation of coalitions opposing Louis XIV’s France.

1685-1715: Containment of the “Sun King”

The final 30 years of Louis XIV's reign, from 1685 to 1715 were marked by a series of conflicts that tested France's hegemony in Europe and strained the absolute monarchy. This phase commenced with the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which had granted rights to French Protestants, thereby leading to religious tensions and an exodus of Huguenots. Meanwhile, on the geopolitical front, Louis XIV's territorial ambitions sparked widespread alarm across Europe, resulting in the formation of grand alliances to counter French expansion. The protracted warfare, including the War of the Spanish Succession, placed significant economic burden on France, leading to fiscal crises, public dissatisfaction, and food shortages. Despite these struggles, Louis XIV's reign continued to exert profound cultural influence, with France setting the pace for European arts, literature, and philosophy. [Though the map makes it look like an even match, in actuality the War of the Spanish Succession was waged primarily by 1) Bourbon France and 2) newly-Bourbon Spain against 1) Britain, 2) the Dutch Republic, 3) the Holy Roman Empire, 4) Prussia, 5) Portugal, 6) Savoy, and 7) anti-Bourbon, pro-Habsburg Spain]

[Though the map makes it look like an even match, in actuality the War of the Spanish Succession was waged primarily by 1) Bourbon France and 2) newly-Bourbon Spain against 1) Britain, 2) the Dutch Republic, 3) the Holy Roman Empire, 4) Prussia, 5) Portugal, 6) Savoy, and 7) anti-Bourbon, pro-Habsburg Spain]

October 25, 1685: Publication of the Edict of Fontainebleau, which revoked the limited tolerance and rights granted to French Protestants. The edict has immense implications for the course of French history, as large numbers of French Protestants emigrated leading to a sort of “brain drain”, to the detriment of France and the benefit of her enemies. It also planted the seed of a renewed drive toward achieving tolerance of Protestantism through both popular and political channels — not merely through the whims of one king.

September 27, 1688-September 1697: The Nine Years’ War, or the War of the Grand Alliance, saw Louis XIV’s armies cross the Rhine River and invade the territories of the Holy Roman Empire. This aggressive act, along with the French army’s brutal tactics, stimulated the formation of the Grand Alliance (also called the League of Augsburg) to oppose him militarily. This war marked, if not a decline, the plateauing of France’s power under Louis XIV.

December 20, 1689: Formation of the Grand Alliance in the Hague, in the Dutch Republic, with the coalition parties including the Austrian Habsburg Empire, the Dutch Republic, England, Spain after 1690, and Savoy from 1690 to 1696. These powers would face down Louis XIV’s France in the Nine Years’ War and again in the War of the Spanish Succession, though with Spain no longer being a member of that Second Grand Alliance.

1699: Publication of the book Les Aventures de Télémaque by François Fénelon, Archbishop of Cambrai, and, since 1689, tutor to the 7-year-old Duke of Burgundy (grandson of Louis XIV and second in line to the French throne). In the novel, the tutor character Mentor instructs his pupil Telemachus in the principles of good and just government, including the suggestion of a major overhaul of the ruling regime, the elimination of the mercantile system and taxes on the peasants, the ceasing of armed conflict, and puts forward the idea of a parliamentary system of government and an international Federation of Nations to handle quarrels between nations peacefully. Wildly popular, the book is a seminal work of the Enlightenment and a not-so-veiled attack on the absolutist Ancien Regime system in France at the time.

July 9, 1701-February 6, 1715: The War of the Spanish Succession, an actual global war, is waged primarily between France and Bourbon Spain on one side and Britain, the Dutch Republic, the Holy Roman Empire, and pro-Habsburg Spain on the other. It is a long, devastating, and exhausting war that ends with the French Bourbon grandson of Louis XIV — Philip of Anjou — being allowed to succeed to the throne of Spain as Philip V, though with any governmental ties or plans of a union of French and Spanish empires completely out of the question. In return, the Grand Alliance powers detached the Spanish Netherlands and much of Spain’s territorial possessions in Italy, giving them to Habsburg Austria, while Britain gained Gibraltar and Menorca. The settlement ending the war established a balance of power that would prevail among the European Great Powers up until the outbreak of the French Revolution and the revolutionary wars in 1789-1792.

September 1, 1715: King Louis XIV dies and Louis XV becomes king at the age of five.

1715-1789: The Last Bourbon Kings

The era from 1715 to 1789, encompassing the rule of the last Bourbon Kings, Louis XV and Louis XVI, stands as a period of substantial political, social, and intellectual ferment leading to the revolutionary upheavals of France. Following the grandeur and absolutism of Louis XIV's reign, his successors found themselves forced into a precarious balancing act ruling a kingdom marked by escalating financial crisis, rising social inequality, and the rapid dissemination of Enlightenment ideas that increasingly challenged the monarchy's divine right. Louis XV's reign, although initially characterized by an attempt at reform and modernization, ended in public disillusionment and decline, setting the stage for Louis XVI. His rule, while marked by indecisiveness and unsuccessful attempts at fiscal and social reform, was pivotal in the lead up to the French Revolution.

[The Battle of Fontenoy, fought on May 11, 1745, pitted France under the overall command of Maurice de Saxe against a coalition of the Dutch, British, Austrians, and Hanoverians, in the War of the Austrian Succession. It's been said Napoleon stated that Saxe's victory at Fontenoy extended the life of the Old Regime in France]

1715-1756: The ‘Good Times’ of Louis XV’s Reign

The initial years of Louis XV's reign, spanning from 1715 to 1756 marked a period of relative prosperity and peace, setting it apart from the latter half of his rule. Upon ascending to the throne as a child, the young Louis XV’s realm was administered by the Duke of Orleans as Regent and later, after 1726, by Cardinal Fleury, his Chief Minister. Under their guidance, France witnessed a period of internal stability, economic recovery, and diplomatic successes, largely maintaining its status as a dominant European power following "the Sun King's" passing. The king himself, known for his charm and charisma, enjoyed immense popularity among his subjects during these early years. However, this golden era was not devoid of its challenges, as old systems of governance began to reveal their cracks and Enlightenment ideas started permeating societal discourse, as well as religious controversies like Jansenism.

May 2, 1716: Creation of the General Bank and the Compagnie d'Occident, marking the beginning of Law's system, named after the Scotsman John Law. The system was quite advanced for Old Regime France, but its collapse in June 1720 would later undermine any idea of creating a central French bank like the Bank of England.

June 24, 1719-December 14, 1720: John Law is named superintendent of the currencies on June 24, 1719. That same year, Law became the architect of what would later be called the Mississippi Bubble, an event that would begin with the consolidation of the various trading companies of Louisiana into a single monopoly — the Mississippi Company — with thousands upon thousands of company shares issued. On January 5, 1720, Law was made Comptroller-General of Finances. Unfortunately, this scheme leads to rampant speculation, followed by panic, as people flooded the market with future shares trading as high as 15,000 livres per share, while the shares themselves remained at 10,000 livres each. By May 1720, prices fell to 4,000 livres per share, a 73% decrease in one year. The rush to convert paper money to coins led to sporadic bank runs and riots. Squatters now occupied the square of Palace Louis-le-Grand and openly attacked the financiers that inhabited the area. It was under these circumstances and the cover of night that John Law fled from Paris, on December 14, 1720, leaving all of his substantial property assets in France. His fall coincides with the collapse of the General Bank (Banque Générale) and subsequent devaluing of the Mississippi Company's shares.

October 25, 1722-February 23, 1723: Coronation of Louis XV at Reims Cathedral takes place on October 25, 1722. But it wouldn't be until February 23, 1723, that Louis XV is declared of age to rule. This officially marks the end of the regency, however, the Duc d'Orléans remained in office as Prime Minister until his death in December 1723.

June 21-August 19, 1726: Fall of the prime minister, the Duke of Bourbon, and his replacement on June 25 by Cardinal de Fleury (1653-1743). Under Fleury's auspices, the General Farm (or General Tax Farm; Ferme générale in French) is restored on August 19, after the institution foundered due to Louis XIV's financial difficulties between 1703 and 1726.

June 24, 1730: Declaration establishing the Bull Unigenitus as a law of the Kingdom of France. This bull issued by Pope Clement XI condemns Jansenism, and it proves to be very controversial and divisive. Jansenist opposition to it and the movement in general help contribute the the growth of the public sphere and public opinion through numerous press publications, helping create the conditions for the revolutionary press and public sphere in the lead-up and during the French Revolution.

August 1732: Crisis in the parlements: Prime minister Cardinal Fleury compels parliaments to register the Bull Unigenitus. Louis XV declared: “The power to make laws and to interpret them is essentially and solely reserved to the king. Parliament is only responsible for overseeing their execution."

July 8-October 20, 1740: A conflict originating between Britain and Spain, called the War of Jenkins' Ear, expands into a larger conflict when Fleury informs the British ambassador that Louis XV has decided to intervene on behalf of Spain, on July 8, 1740. In August, Cardinal Fleury sends two squadrons to America to help Spain in conflict with Great Britain. But then this conflict expands even further into a wider European war when, on October 20, 1740, the Austrian Habsburg Emperor Charles VI dies without male heirs, triggering the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748).

January 29, 1743: Death of Cardinal Fleury and the beginning of Louis XV's rule without a prime minister. He makes moves to break up the patronage empire that Fleury had put together and nobody was allowed to occupy the same kind of position Fleury held in terms of patronage and access to the king. Under Louis XV, advisory consultations and policy matters were kept largely out of sight, while foreign policy matters were managed via the the so-called Secret du Roi — secret diplomatic channels used by Louis XV throughout his reign.

April 24-October 18, 1748: France, by early 1748, had conquered most of the Austrian Netherlands, but a British naval blockade was crushing their trade and the state was close to bankruptcy. This stalemate finally resulted in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, with a diplomatic congress assembling on April 24, 1748, and the actual signing of the treaty occurring on October 18. Although the treaty confirmed Maria Theresa in her titles, it failed to address underlying tensions between the signatories, several of whom were unhappy with the terms. France obtained minimal gains despite performing well on the battlefield and expending vast amounts of money, while the Spanish failed to recover Menorca or Gibraltar, which had been ceded to Britain in 1713. The result of this unsatisfactory treaty was the realignment known as the Diplomatic Revolution, in which Austria and France ended the age-old French–Habsburg rivalry that had dominated European affairs for centuries, while Prussia allied with Great Britain. These changes set the stage for the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756.

February 17-27, 1750: The Duke of Richelieu suspends the Estates of Languedoc — a representative provincial assembly — by order of the king. On February 27, the assembly was suspended indefinitely by decision of the Council of State. This marks another step by the absolutist royal government to eliminate alternative, traditional sources of legislative authority in the Kingdom of France.

July 1, 1751: Publication of the first volume of the Encyclopédie, a major literary and intellectual work of the Enlightenment. Its editing and publication is mainly overseen by Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d'Alembert.

1756-1789: Bourbon Monarchy on the Rack

The period from 1756 to 1789 represents a time of escalating crisis for the Bourbon monarchy, as France, under the reign of Louis XV and later Louis XVI, grappled with a myriad of financial, social, and political challenges that strained the traditional structures of the Ancien Régime. This era, marked by significant events such as the Seven Years' War, the loss of colonial territories, and the costly involvement in the American Revolution, placed a severe economic burden on the kingdom. Simultaneously, the conspicuous consumption of the aristocracy and the inability of the monarchy to effectively implement fiscal and social reform exacerbated socio-economic disparities. These factors, coupled with the proliferation of Enlightenment ideas questioning monarchical absolutism and advocating for civil liberties, eroded public confidence in the monarchy.

[Scene from the Siege of Yorktown (1781), the decisive and culminating campaign of the American War of Independence, whose victory owed a lot to America's French allies. Unfortunately, finance minister Turgot's ominous words from before the conflict proved true: "The first gunshot will drive the state to bankruptcy"]

May 17, 1756: Beginning of the Seven Years' War (1756-1763, although fighting had been going on in French and British North America since 1754). This massive, exhausting, and global war would end with the complete defeat of France and the loss of several colonies, most notably its continental possessions in North America, although the Caribbean colonies the French retained were far more profitable than their territories in Canada and the Ohio Valley. Still, it was the damage to national honor and the huge debts accrued from the war that severely undermined the French state.

January 5, 1757: Would-be assassin and servant Robert François Damiens attacks King Louis XV with a harmless stroke of the penknife to warn him to think better about his duties. He is drawn and quartered in the Place de Grève on March 28. The rumour, stirred up by the Jansenists, falsely denounced it as a Jesuit plot. In tje wale of the attack, the depressed king backtracked. Stunned for a moment by the Damiens attack, provincial parlementarians once again affected from May to September 1757 a protest attitude vis-à-vis royal taxation, in solidarity with their Parisian colleagues.

November-December, 1758: François Quesnay publishes his Economic Table at Versailles. The book presents an economic model that laid the foundation of the Physiocratic school of economics. Quesnay believed that trade and industry were not sources of wealth, and instead argued that agricultural surpluses, by flowing through the economy in the form of rent, wages, and purchases were the real economic movers. Though his economic model wasn't necessarily capitalist, it did signify a break with the more mercantilist economic models of the time.

January 20-25, 1759: Lettres de cachet order the exile of 22 parlementaires from Besançon, who were in conflict with the intendant and first president of the Parlement of Besançon, Bourgeois de Boynes. On January 21 and 22, they are dispersed to different fortresses. Eight other councilors are exiled in turn on January 25, and the exile wouldn't end until April 1761.

September 20, 1759: A lit de justice is held by the Louis XV at Versailles for the registration of the September financial edicts. The Comptroller General of Finance — Etienne de Silhouette — attempts a tax reform, known as the general subsidy, a set of measures which leads to the taxation of income from all social categories.

September 22-November 23, 1759: Louis de Bourbon-Condé, Count of Clermont, holds a lit de justice at the Court of Aids to enforce the registration of three fiscal edicts. The court issued severe remonstrances, calling for a coherent financial policy and denouncing the continual propagation of new, arbitrary regulations. The court wants "a fixed and certain law in the taxation of land and other buildings, a proportional and non-arbitrary law in the taxation of the person, a uniform law in the taxation of consumption". The general subsidy project fails in the face of the hostility of the privileged estates/orders as well as the aggravation of the mass of taxpayers. On November 13, the Court of Aids sends the king a new remonstrance on the extension of the twentieth provided for in the general subsidy. An early bankruptcy brings Silhouette down on November 23. Bertin, who replaces him as Comptroller-General, abandons the general subsidy but proposed the same types of taxation, direct or indirect, in particular the additional twentieth and the sol per livre of the General Farm.

July 4, 1760: The Parlement of Rouen issues a remonstrance of that calls for the restoration of the Estates of Normandy and proposes the motto, "A King, a law, a Parlement." It's one of the earlier calls for the re-establishment of the old provincial estate bodies, which had been gradually eliminated as absolutism took firmer hold in France since 1589.

November 13, 1761: Opening of the trial against the Calas family, brought by the Capitouls of Toulouse — a classic case of superstition and religious authority expanding outside its proper remit. Voltaire defends Jean Calas, a Huguenot condemned without evidence for having killed his son whom he suspected of wanting to convert to Catholicism; in reality, his son committed suicide. Voltaire's campaign against the Parlement of Toulouse for prosecuting and condemning Calas epitomizes several of the ideals of the Enlightenment.

February 10, 1763: Signing of the Treaty of Paris, ending France's participation in the Seven Years' War and included major French colonial cessions to Great Britain, such as the transfer of Canada, part of Louisiana, the Ohio Valley, Dominica, Tobago, Grenada, Senegal, and its Indian Empire to Great Britain. It marks the end of the first French colonial phase, though it did retain some highly profitable Caribbean colonies like Martinique, Guadeloupe and Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti). Another crucial outcome of the lost war is that France accrued massive debts, which it would struggle to repay for years, especially when French involvement in the American Revolutionary War added another huge load of state debt.

June 5, 1764: Start of the Brittany Affair, which featured a showdown pitting the Breton Parlement and the Estates of Brittany against the authority of the French monarchy over an issue of taxation. Two of the main protagonists were La Chalotais (procureur général) at the Parlement of Brittany versus the royal governor of the province, the duc d'Aiguillon.The affair has been seen as a precursor of the French Revolution.

November 26, 1764: In the aftermath of the La Valette affair (1761), the parlements, expressing their Jansenist, Gallican, and regalist sympathies, succeed in imposing on Louis XV the expulsion of the Society of Jesus — the Jesuits. This resulted in 106 Jesuit colleges being converted to other uses and France’s expulsion was part of a wider European trend of expelling the Jesuits, often justified by the argument that they had accrued so much power that they constituted “a state within a state.”

March 3, 1766: The “Sitting of the Flagellation” or the “Scourging Session” occurs, in which, in a lit de justice, King Louis XV bluntly tells the Parlement of Paris that they have no authority over legislation and all power flows solely from Louis XV’s absolute rule. This session came in response to continued resistance of members of the parlements over the Brittany Affair.

September 16, 1768: René Nicolas de Maupeou becomes Keeper of the Seals of France, a key role that assists the Chancellor of France in ensuring that royal decrees were enrolled and registered by the judicial parlements. Maupeou’s position would eventually lead to a major conflict between the parlements and central royal government in the early 1770s.

May 8-August 15, 1769: French forces defeat Corsican politician and freedom fighter Pascal Paoli on May 8, leading to the complete conquest of Corsica by France. Months later, on August 15, Napoleon Bonaparte was born on the island of Corsica.

April 19, 1770: The future Louis XVI marries Marie-Antoinette of Austria by proxy in Vienna.

January 21, 1771: Part of Maupeou's coup or the Maupeou Revolution, the parlementaires of the Parlement of Paris are exiled to Troyes. The parlements, which had opposed the royal edicts, were restructured and deprived of their political prerogatives. Confronting their resistance to the financial reforms of Abbé Terray, Maupeou condemns the obstinance and unity of the body of the parlements. Then, faced with their refusal to submit to the royal authority, Maupeou orders the resumption of parlementary activities by force, dispatching musketeers to the residences of the magistrates to banish them and confiscate the charges of parlementaires who refused.

May 10, 1774: King Louis XV dies of smallpox and his grandson, Louis XVI, succeeds to the throne. The new king goes about reforming various parts of the ministry.

August 24-26, 1774: The so-called “Saint-Barthélemy of Ministers” takes place (“Saint-Barthélemy” is a reference to the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572). This leads to the disgrace and downfall of Maupeou, who’s forced into exile on his lands, while Miromesnil becomes the new Keeper of the Seals. The comptroller-general Terray was fired and Turgot moved from the Navy ministry to become the new Comptroller-General of Finances. When he leaves office, Terray leaves a healthy financial situation. The budget deficit was reduced, from 100 million livres in 1769, to 30 million in 1774, and to 22 million in 1776. On August 26, Turgot added Minister of State to his portfolio of positions.

September 13, 1774: Turgot restores the liberalization of the grain trade, a policy previously carried out by Louis XV's prime minister Étienne-François de Choiseul (in office from 1758 to 1770) between the years 1763 and 1770. The significance of the liberalization of the grain trade in Old Regime France is that it marked a major change in economic and government policy from the past: Since grain (and, thus, bread) was the staple diet of the peasantry and the urban population, the French royal government saw food security as an essential duty and therefore heavily controlled the grain trade to ensure the national and local balance between demand and supply; however, with the growth of more liberal economic ideas during the Enlightenment (e.g., Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations) a group called the Physiocrats pushed for a "free market" approach to the grain trade as being the most optimal policy in economic terms. On paper, this capitalist approach to the grain trade made sense, but in practice it unfortunately gave rise to speculators who aimed above all for the greatest profit, which led to hoarding of grain to increase its price and/or buying grain from regions where it was cheap and selling in other regions where it was expensive. These results were what led to the repeal of the first liberalization of the grain trade by Choiseul in 1770. Turgot's restoration of the "free market" approach would soon blow up in his face.

November 12, 1774: The new King Louis XVI brings an end to Maupeou's coup and restores the old parlements. But instead of showing any appreciation for their restoration, the members of the parlements are even more wary of French royal power. Crucially, it was during the Maupeou coup of 1771-1774 that the first calls for convening the national Estates-General take place.

April 18-May 6, 1775: The so-called "Flour War" (Guerre des farines) takes place when, after a poor harvests in 1773 and 1774 combined with Turgot's freeing-up of the grain trade, leds to bread shortages, skyrocketing prices, and hoarding by speculators. Riots and revolts by peasants and city-dwellers erupted in the northern, eastern and western parts of the kingdom of France. Many common Frenchmen see the "free market" approach to the grain trade as disrupting the "moral economy", meaning that it undermined the principle of the royal government ensuring food security for all its subjects. The "Flour War" once again discredits the liberalization of the grain trade in the eyes of both the royal government and the common people, leading Turgot to reestablish price controls on grain and repeal the act in 1776.

April 19, 1775: The Battles of Lexington and Concord between Massachusetts colonial militia and British regulars marks the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. Three years later, France would officially ally with the American insurgents and directly intervene on their behalf in the war.

January 5-March 12, 1776: Turgot proposes to the royal council, on January 5, the abolition of the corporations — coporations in Old Regime France refers to guilds and professional associations like those for lawyers or doctors, which were compulsory and highly regulated, and therefore stifled capitalist, entrepreneurial spirits from being able to whatever they want business-wise — and the royal corvée (essentially a forced labor tax the peasantry had to carry out). Again, while Turgot's intentions were well-meaning, these liberal economic policies provoke strong resistance from the guilds and other corporative societies because it means the loss of many of their traditional privileges. This resistance induces Louis XVI to hold a lit de justice on March 12 to force the registration of Turgot's edicts.

May 12-13, 1776: Facing serious hostility from both political circles (such as remonstrances of the Parlement of Paris) and commercial circles, Turgot resigns. He is replaced by Clugny de Nuits who revokes all reforming edicts over the next six months. At the same time, more observant and intelligent Frenchmen begin to see these privileged corporative bodies as selfish and obstructing greater freedom in society.

July 4, 1776: The Americans declare their independence.

October 22, 1776: The Geneva banker (and seeming financial wizard) Jacques Necker is appointed Director General of the Royal Treasury. As a Protestant, he could not be a member of the King's Council and thus could not be appointed Comptroller-General of Finances, hence the alternative title. In order to tackle the budgetary difficulties resulting from France's still unofficial support for the American rebels, Necker resorts to raising loans both domestically and on international money markets, while at the same time but will returning to the policy of "economies" (aka belt-tightening) carried out by Turgot.

December 28, 1776: The American ambassador Benjamin Franklin is received by Foreign Minister Vergennes, asking for help from France in their fight against the British.

April 26, 1777: The Marquis de Lafayette departs France for the United States. He eventually lands on North Island near Georgetown, South Carolina on June 13, 1777.

June 29, 1777: After the resignation of Taboureau des Réaux , Necker is appointed Director-General of Finances (again because of his Protestantism, it's an alternative title but essentially the same as Comptroller-General). He will launch a series of loans to finance the French war effort in the American Revolution.

December 17, 1777: King Louis XVI recognizes the independence of the United States, becoming the first head of state in the world to do so.

January 30-February 6, 1778: Treaty of Amity and Commerce Between the United States and France is concluded on January 30, with each country promising to grant the other the most favored nation clause. The treaty sets out the principle of the freedom of the seas and the right of neutral states to trade with nations at war. Then on February 6, a second treaty — the Treaty of Alliance — intended to remain secret, is signed between France and the United States. It's technically a defensive alliance in case war breaks out between France and Britain. Notably, the treaty stipulates that neither party can make a peace or truce with Great Britain without first obtaining the consent of the other (a promise which the Americans would later break in order to make peace with Britain and bring an end to the war in 1783).

April 12, 1779: Treaty of Aranjuez is signed, renewing of the Family Pact between the Bourbon monarchs of Spain and France. In the treaty, France promises Spain the recovery of Gibraltar, Menorca, Mobile, and Pensacola, lost in various wars against Great Britain over the course of the 18th century.

June 16-July 6, 1779: Charles III of Spain declares war on Great Britain on June 16, shortly followed by the beginning of the siege of Gibraltar by France and Spain on June 24. A Franco-Spanish fleet of 66 vessels and 14 frigates meets in Corunna, on June 25, under the orders of Count d'Orvilliers. On July 2, French forces under the command of Comte d'Estaing defeat British forces and capture the island of Grenada. Later, on July 6, in the Naval Battle of Grenada, d'Estaing 's fleet defeats a British one commanded by John Byron, enabling French control of the Caribbean Sea and allows the regiments of the French army, commanded by Rochambeau, to land on American territory.

August 8, 1779: An edict abolishes the right of mortmain and personal servitude (serfdom) in the king's royal domains.

February 25, 1780: the Paris Parliament registers the February edict extending the second vingtième and 4 sols per pound of the first vingtième until 1790. The vingtième ("twentieth") was an income tax during the Ancien Régime, based on revenue and required 5% of net earnings from land, property, commerce, industry, and official offices. The vingtième was enacted to reduce the royal deficit. Its eventual expiration date would become a pressing issue in the future, when in the lead-up to the French Revolution the government tried to figure out how to avoid a national default on its debts.

May 2-July 11, 1780: Rochambeau and his expeditionary force of 5,000 men leave Brest, on May 2, and cross the Atlantic. On July 11, Chevalier de Ternay's squadron — carrying Rochambeau's expeditionary force — arrives at Newport, Rhode Island.

February 19, 1781: Necker publishes his Compte rendu au roi (A Report to the King), revealing the state of public finances. Since 1777, Necker had launched 29 loans for a total amount of 530 million livres. By distributing this text with the agreement of Louis XVI, Necker aims to disarm his critics at court. However, the disclosure of the list of pensions granted to courtiers caused a scandal. Not only that, the Compte rendu au roi was manipulated by Necker to show a surplus, when in reality, he merely put the expenditures and debts from the American Revolutionary War in the extraordinary account. But the general public doesn't know that, so when the French royal government finds itself in dire financial straits in the late-1780s, many Frenchmen don't understand how this crisis came about and call for the return of Necker.

May 19-21, 1781: Necker resigns after Louis XVI refuses his ultimatum to put him on the King's Council and returns to Geneva. On May 21, Jean-François Joly de Fleury is appointed Comptroller-General of Finances.

May 22 , 1781: Proclamation of the Edict of Ségur, which requires four degrees of nobility from candidates in the army. Thus, it reserves for the nobility (especially the older nobility) direct access to the ranks of officers without prior service or without passage through military schools. Ségur's edict was meant to provide poor, old noble families with access to a professional military career as opposed to military offices being bought by upstart new nobles. However, the edict also manages to increase tensions between the bourgeoisie and the nobility because the former see it as an attack on them, and just another sign of how unfair and arbitrary both the society of estates and royal absolutism are.

September 28-October 19, 1781: The siege of Yorktown is waged by Franco-American forces, with Lord Cornwallis finally surrendering on October 19 when his position becomes hopeless after the French naval victory in the battle of the Chesapeake prevents British reinforcements from reaching him. This marks the end of major land campaigning on the North American continent, though not the end of the war entirely.

July 2, 1782: Vergennes, who was one of the loudest voices calling for French intervention on behalf of the republican American revolutionaries, sends an army to crush the Geneva Revolution of 1782, which sought to replace the aristocratic republic with a truly democratic republic. On July 2, revolutionary Geneva surrenders. The Geneva Revolution would prove to be important in the lead-up and during the French Revolution, as several Genevan revolutionary exiles would become leaders in France's revolution in 1789.

September 3, 1783: The signing of the Treaty of Paris puts an end to the American War of Independence. Peace between France, Spain, and Britain is also concluded at the Treaty of Versailles. Britain returns Menorca and Florida to Spain, but retains Gibraltar. France recovers its trading posts in India and Senegal, and Great Britain cedes some islands to it in the West Indies. Though France partially got its revenge on Britain for the disastrous Seven Years' War, the debts and deficits run up by its involvement in the American war would come back to haunt the royal government in 1786.

April 27, 1784: The first public performance of The Marriage of Figaro by Beaumarchais. Its significance derives from the fact that the play questions social inequalities: One of the last lines in the play is, “Nobility, fortune, rank, places, all of this makes you so proud! What have you done for so many goods? you took the trouble to be born, and nothing more." The eventual revolutionary Danton stated that "Figaro has killed the nobility!", while Napoleon is supposed to have called it "the Revolution already put into action."

November 3, 1783: Charles Alexandre de Calonne is appointed to the position of Comptroller-General of Finances. He is determined to figure out how to address the glaring problem of France's national debt. Indeed, interest on accumulated debts absorbs more than 50% of the budget. State revenue reached 475 million livres, against 587 million in expenditure, equaling a deficit of 112 million livres.

August 10-11, 1784: Cardinal de Rohan, in a misguided attempt to win the favor of Queen Marie-Antoinette who doesn't like him, meets Madame de la Motte, who becomes his mistress and later involves him in a plot to act as an intermediary to purchase a fabulous diamond necklace. In January 1785, the Cardinal de Rohan negotiates the purchase of the necklace, but Jeanne de la Motte actually made up this entire scheme of pleasing the Queen and, with her fellow conspirators, take the necklace and sell the diamonds on the black market.

August 15, 1785: Cardinal de Rohan is arrested within the Versailles palace as he was preparing to say mass, interrogated personally by the king, placed under arrest, and marched off in his full cardinal’s attire through crowds of courtiers to the Bastille prison. The reason for this: The discovery of a sordid yet trivial scandal involving a diamond necklace, the Cardinal de Rohan, and a confidence woman that exploded into a public relations fiasco — The Affair of the Diamond Necklace.

May 31, 1786: In a bread-and-circuses of a trial, the court acquits Cardinal de Rohan of any wrongdoing in the Affair of the Diamond Necklace, instead focusing their punishment on the confidence woman, Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy, alias Jeanne de la Motte, who set up the whole scheme. Public opinion is very much on the side of the Cardinal. Unfortunately, Marie-Antoinette took the acquittal very personally and ensured, through her husband, that the Cardinal de Rohan was exiled to the Abbey of la Chaise-Dieu.

August 20, 1786: Calonne presents to Louis XVI his Précis sur l'administration des finances, which proposes an audacious program of administrative and fiscal reforms inspired by that of Turgot. It includes the creation of the territorial subvention, land tax payable by the nobility and the clergy, conversion of the corvée (essentially a forced labor tax) into a tax in cash, abolition of internal customs, freedom of trade in grain, creation of provincial and municipal assemblies elected by suffrage censitaire without distinction of order.

November 29, 1786: King Louis XVI convenes the Assembly of Notables to meet in 1787, primarily to present Calonne's financial reform program.

February 22-May 25, 1787: The convocation of the Assembly of Notables by the king and his chief minister Calonne — the first meeting of the Assembly of Notables since 1626. Calonne's plan to get his reform scheme the go-ahead from the Assembly of Notables fails, due to a combo of distrust of Calonne and the fact that the Assembly of Notables doesn't represent France, and therefore cannot legislate any fiscal reforms and taxation — only the Estates-General, the Assembly says, can do that.

February 19, 1788: Creation of the Society of Friends of Blacks by journalist and revolutionary Brissot, which advocates for the abolition of slavery in French colonies.

May 3, 1788: The Parlement of Paris, feeling threatened with suppression by the royal government, takes the lead and by a decree, spearheaded by Jean-Jacques Duval d'Eprémesnil, which spells out what the Parlement saw as the fundamental laws of the realm, emphasizing "the right of the Nation freely to grant subsidies through the organ of the Estates-General regularly convoked and composed," plus the right of the parlements to register new laws, and the freedom of all Frenchmen from enduring arbitrary arrest (e.g., lettres de cachet); the message also emphasizes the importance of intermediate bodies linked to the society of orders (or estates) as the essential character of the monarchical constitution. This view of the fundamental laws of the realm is in opposition to the ideals of absolutism.

May 5-6, 1788: The Marquis d'Agoult, captain of the guards, attempts to arrest the councilors Epremesnil and Montsabert in the middle of a session. Protected by their colleagues, they manage to escape but ultimately give themselves up the next day.

June 7, 1788: The Day of the Tiles (Journée des Tuiles) in Grenoble occurs; arguably the first open revolt against the king and royal policies pushed through by Étienne Charles de Brienne, minister of finance from 1787 to 1788.

July 21, 1788: The Assembly of Vizille convenes what in actuality is essentially the Estates-General of Dauphiné. Claude Perier, inspired by all of the liberal ideas around him, assembled a meeting in the room of the Jeu de Paume (indoor tennis court) in his Chateau de Vizille and hosted this meeting, which was previously prohibited in Grenoble. Almost 500 men gathered that day at the banquet hosted by Claude. In attendance there were many "notables" including churchmen, businessmen, doctors, notaries, municipal officials, lawyers, and landed nobility of the province of Dauphiné. The demands sounded out at this meeting aligned with the sentiments of many Frenchmen: The convocation in Paris of the national Estates-General, echoing some prominent voices in the Assembly of Notables (like Lafayette) as well as the calls for the Estates-General dating back to the exiled members of the parlements during Maupeou's coup (1771-1774), when he tried to completely restructure the court system and neutralize the power of the judiciary. What's important about the Assembly of Vizille is that it marks a step toward far more open opposition to the absolutist monarchy. with increasing support for its demands from diverse corners of society. Two lawyers who led much of this meeting would go on to play critical roles in the early phases of the Revolution: the Protestant Antoine Barnave and Jean-Joseph Mounier.

August 8, 1788: The royal treasury is declared empty, and the Parlement of Paris refuses to reform the tax system or loan the Crown more money. To win their support for fiscal reforms, the Minister of Finance, Brienne, sets May 5, 1789, for a meeting of the Estates-General, the national assembly of the three estates (or orders) of the realm:

- The First Estate: The Clergy

- The Second Estate: The Nobility

- The Third Estate: Commoners (ranging from peasants to wealthy bourgeoisie; basically defined as those that don't belong to either the First or Second Estate)

August 16, 1788: The treasury suspends payments on the debts of the government. As a result, the Paris Bourse (stock exchange) crashes.

August 25, 1788: Brienne resigns as Minister of Finance, and is replaced by the Swiss banker Jacques Necker, who is popular with the Third Estate, in part because he seemingly financed France's involvement in the American Revolutionary War while at the same time producing a surplus on the balance sheet. French bankers and businessmen, who have always held Necker in high regard, agree to loan the state 75 million, on the condition that the Estates-General will have full powers to reform the system.

December 27, 1788: Over the opposition of the nobles, Necker announces that the representation of the Third Estate will be doubled and that nobles and clergymen will be eligible to sit with the Third Estate.

December 29, 1788: Marseilles calls for an increase in the number of elected members of the Third Estate and also for voting by head in the Estates-General.

II. Timeline of the French Revolution: 1789-1799

As we journey through this timeline of the French Revolution, we will chronicle a turbulent and exciting era marked by monumental events: the fall of the Bastille, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the Reign of Terror, and the rise of Napoleon, among others. These events, while chaotic and often violent, paved the way for the abolition of feudalism, the introduction of secularism and secular education, and the rise of nationalism. It is in these transformative instances that we observe not only the shifting landscape of France but also the undercurrents of change that were rippling across the world.

1789-1794: The Outbreak of Revolution and Its Increasingly Radical Course

Delving into the tumultuous period of 1789 to 1794, we encounter one of the most defining chapters of the Bourbon Dynasty — the French Revolution. This critical juncture not only reshaped the political, social, and economic landscape of France, but it also sent seismic waves across Europe and beyond, heralding the beginning of modern political ideology.

Rooted in widespread civil unrest and financial crisis, and led by an intellectual vanguard schooled for years in the writings of the Enlightenment, the revolution marked the end of absolute monarchy and the rise of radical social change in France. From the storming of the Bastille to the Reign of Terror, this phase of the Bourbon Dynasty is marked by extraordinary turmoil, its overthrow, and a shift in power that would eventually pave the way for the era of Napoleon Bonaparte.

1789: Estates-General, the Bastille, and the Constituent Assembly

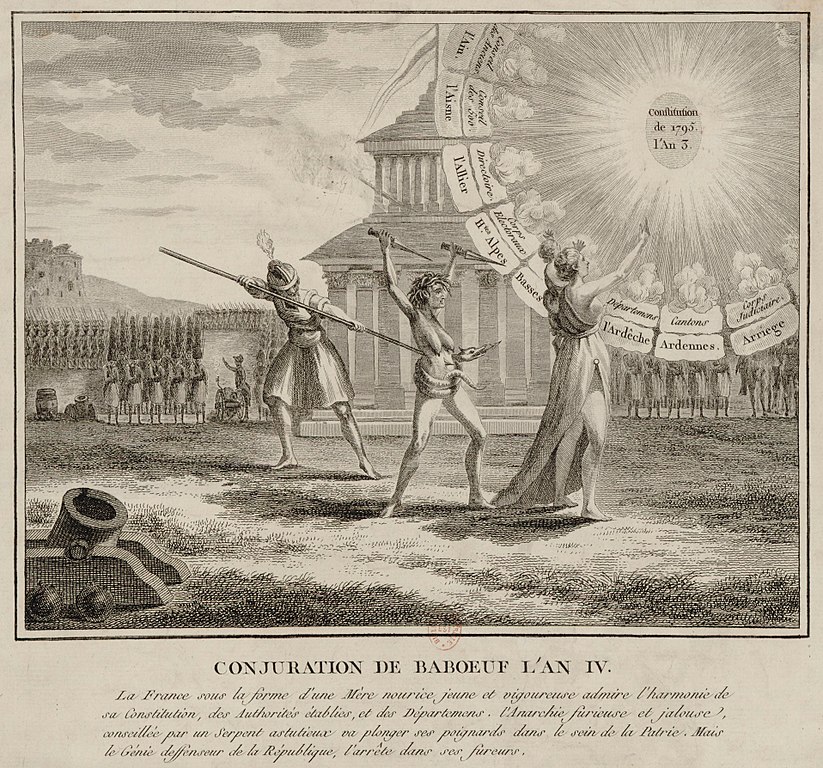

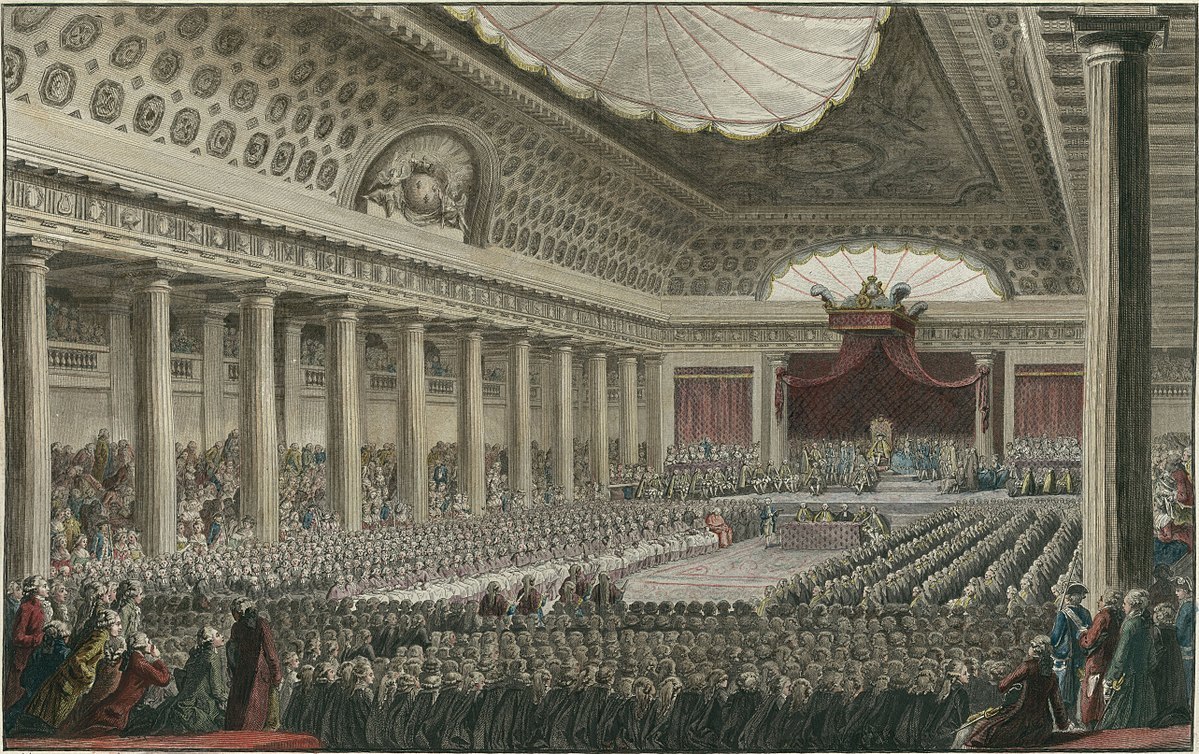

[The assemblage of the national Estates-General in Versailles in May 1789 — the first time this once significant body met in 175 years]

January 1789: French intellectual, writer, and member of the clergy Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès publishes his famous and highly influential political pamphlet, What Is the Third Estate? (Qu'est-ce que le Tiers-État?).

February 7, 1789: Orders for the estates to draw up customary notebooks of grievances (cahier de doléances) in anticipation of the meeting of the Estates-General.

April 27, 1789: Riots occur in Paris, fueled by workers of the Réveillon wallpaper factory in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine who mistook a statement about fixing wages at a liveable level as meaning that wage cuts were about to take place. Twenty-five workers were killed in battles with police.

April 30, 1789: Deputies to the Estates-General from Brittany (Bretagne), including Le Chapelier, Lanjuinais and Glezen, lawyers at the bar of Rennes, establish the Breton Club at Versailles. The Breton Club would eventually evolve into the far more famous Jacobin Club.

May 2, 1789: The presentation by order of the 1,200 deputies to King Louis XVI at Versailles, during the grand opening procession of the Estates-General.

May 5, 1789: The Estates-General convenes for the first time since 1614. The Estates-General was nominally convoked by finance minister Jacques Necker to help solve the kingdom's dire financial straits. However, very soon, the representatives elected to the Estates-General move beyond this narrow remit and discuss the implementation of political, not just fiscal, reforms.

June 3, 1789: The scientist Jean Sylvain Bailly is chosen the leader of the Third Estate deputies.

June 10-14, 1789: At the suggestion of Sieyès, the Third Estate deputies decide to hold their own meeting, and invite the other Estates to join them. Nine deputies from the clergy decide to join the meeting of the Third Estate on June 13-14, 1789.

June 17, 1789: The Third Estate votes to leave the Estates-General and form a new body of government, calling itself the National Assembly, led by Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau.

June 20, 1789: The famous Tennis Court Oath takes place (Serment du Jeu de Paume). The Tennis Court Oath came about after the bodies comprising the Estates-General — the clergy, the nobility, and the Third Estate — reached an impasse over issues of representation, especially on the question of voting by order or voting by head, the latter of which would benefit the more numerous Third Estate representatives. The Third Estate representatives moved to meet in the royal tennis court because, on the morning of June 20, when they arrived at the chambers of the Estates-General, the door was locked and guarded by soldiers. Interpreting this as an attempt to try and silence them, or outright suppress them, the Third Estate instead held their own congregation in the nearby tennis court, where they swore "not to separate and to reassemble wherever necessary until the Constitution of the kingdom is established."

June 25-27, 1789: Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (later known as Philippe Égalité because of his commitment to the Revolution), leads 48 nobles to join the National Assembly. Partly due to this, on June 27, Louis XVI changes course, instructs the nobility and clergy to meet with the other estates, and recognizes the new Assembly. However, at the same time, Louis XVI orders reliable military units, primarily composed of Swiss and German mercenaries, to gather in Paris.

July 9, 1789: The National Assembly becomes the National Constituent Assembly. After the storming of the Bastille, the National Constituent Assembly became the effective government of France. It dissolved on September 30, 1791, and was succeeded by the Legislative Assembly.

[After the Royal-German regiment, commanded by Prince de Lambesc, had quelled and injured Parisian citizens in the preceding days, the French Guards — whose rank-and-file were heavily local — engaged with the Royal-Germans in front of their depot, at the corner of the Boulevard and the rue de la Chaussée d'Antin, on the night of July 12, 1789. To put it in modern perspective: It would be akin to something like a state's National Guard fighting a detachment of the U.S. Army]

July 14, 1789: A large armed crowd, including both armed civilians and the mutinous French Guards (Régiment des Gardes françaises), besieges and eventually storms the Bastille, which holds only seven prisoners but has a large supply of gunpowder, which was the main objective of the crowd. After several hours of resistance, the governor of the fortress, de Launay, finally surrenders. But as he exits, he is killed by the crowd. The crowd also kills de Flesselles, the provost of the Paris merchants.

August 4, 1789: The Night of August 4, 1789 is the session of the National Constituent Assembly during which the suppression of feudal privileges was voted. Beginning on Tuesday, August 4, at 7 o'clock in the evening, the meeting goes on after midnight, until 2 o'clock in the morning. It is a fundamental event of the French Revolution , because, during the session which was then held, the Constituent Assembly put an end to the feudal system. It abolishes all feudal rights and privileges as well as all the privileges of classes, provinces, cities, and corporations. The main impetus for the initiative comes from the Breton Club, the future Jacobin Club.

August 20-August 26, 1789: The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen de 1789) is drawn up and published. This declaration, crafted by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is one of the preeminent human civil rights documents of the French Revolution and the entire Enlightenment movement in general. Deeply influenced by Enlightenment philosophers — from moderate philosophes like Montesquieu to more radical philosophes like Diderot and d'Holbach — the Declaration was a central statement of the values of the French Revolution at this point. It would have an indelible impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty and democracy in Europe and the world at large.

September 16, 1789: First issue of Jean-Paul Marat's newspaper, L'Ami du peuple, proposing a radical social and political revolution.

October 5, 1789: The Women's March on Versailles, also known the October Days (Journées des 5 et 6 octobre 1789), was one of the earliest and most significant events of the French Revolution. The march began among women in the marketplaces of Paris who were nearly rioting over the high price of bread. The unrest soon became caught up in the activities of revolutionaries seeking liberal political reforms and a constitutional monarchy for France and the mob of women marched from Paris to the royal residence of Versailles. The March on Versailles ended with the crowd forcing Louis XVI, his family, and most of the French Assembly to return with them to Paris.

October 6, 1789: The Breton Club moved to the Couvent des Jacobins rue Saint-Honoré in Paris and took the name of "Society of Friends of the Constitution", before officially becoming the Jacobin club on August 10, 1792. The founders — Lanjuinais and le Chapelier — were joined by Barnave, Duport, Lafayette, Lameth, Mirabeau, Sieyès, Talleyrand, Brissot, Robespierre.

October 10-12, 1789: Deputies of the National Constituent Assembly decree that Louis XVI would bear the title of King of the French, as opposed to King of France. On the same day, Doctor Joseph Ignace Guillotin proposes the use of the guillotine to the Assembly as a more humane and equal form of execution. With the revolution accelerating, the arch conservative brother of Louis XVI, Charles the Comte d'Artois, writes to the Holy Roman (Austrian) Emperor Joseph II, asking him to intervene in France.

November 2-December 24, 1789: Decree on the nationalization of the property of the clergy, proposed by Talleyrand, is adopted by 568 votes against 346 on November 2, placing the property of the clergy of the Catholic Church at the disposal of the nation in order to reimburse the debts of the state. Notably, Necker tries to oppose the confiscation. The next day, the former parlements are put on vacation by decree of the National Assembly and, on November 5, a decree of the National Assembly puts an end to the provincial Estates of Artois. On November 28, Doctor Joseph Guillotin demonstrates to the deputies of the Constituent Assembly his new machine used to execute those condemned to death, stating it's the "safest, fastest, and least barbaric" way to carry out a capital execution. Returning to the nationalization of church property, on December 19, the Assembly approves the creation of assignats, paper certificates pledged on the sale of national property, which eventually turn into currency. On December 22, the Assembly decrees the division of France into departments based on the size of territories and population, eliminating the old and convoluted territorial divisons of the Ancien Regime. And, finally, on December 24, non-Catholics gain citizenship.

1790: Rise of the Political Clubs and Breakdown of the Revolutionary Consensus

[Held on the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, the Fête de la Fédération — July 14, 1790 — saw roughly 400,000 to 600,000 Parisians attend the ceremony at the Champ-de-Mars. Although it was a celebration of liberty, equality, and fraternity, there are eerie aspects to the depiction: 1) The placement of the French army at the center, alongside the Altar of the Fatherland, implying it's essential to the revolution; and 2) the crowds giving the Roman salute, which at this time was of course not associated with fascism...yet would be in the 20th century, along with the fasces — the bundle of spears holding up the canopy on the right]

January 18-22, 1790: Marat publishes a fierce attack on finance minister Necker on January 18. A few days later, on January 22, Paris municipal police try to arrest Marat for his violent attacks on the government, however he is defended by a crowd of sans-culottes and absconds to London. He returns to Paris on May 18, 1790.

February 13-March 12, 1790: The National Assembly passes a number of acts fundamentally altering the way of society as it was under the Old Regime. On February 13, the National Assembly forbids the taking of religious vows and suppresses the contemplative religious orders. Later, on February 23, the National Assembly requires curés (parish priests) in churches all over France to read out loud the decrees of the Assembly. In the area of the military, on February 28, the National Assembly abolishes the requirement that army officers be members of the nobility. On March 8, the Assembly decides on the continuation of the institution of slavery in French colonies, but permits the establishment of colonial assemblies. Returning to the church, on March 12, the National Assembly approves the sale of the property of the church by municipalities.

March 29, 1790: Pope Pius VI condemns the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in a secret consistory.

April 17, 1790: Foundation of the Cordeliers club, which meets in the former convent of that name. It becomes one of the most vocal proponents of radical change.

May 12, 1790: Lafayette and Jean Sylvain Bailly institute the Society of 1789.

May 22, 1790: The Assembly decides that it alone can decide issues of war and peace, but that the war cannot be declared without the proposition and sanction by the King.

June 19, 1790: The National Assembly officially abolishes the titles, orders, and other privileges of the hereditary nobility.

July 26, 1790: It is claimed that Camille Desmoulins published the now famous phrase and national motto of the French Revolution and modern France: Liberté, égalité, fraternité. He supposedly originally coined the phrase on July 14, 1790, during the Fête de la Fédération (Festival of the Federation), which marked the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. On the same day, Avignon, then a territory of the Papal States, asks to be joined to France. The National Assembly, wanting to avoid a confrontation with Pope Pius VI, delays a decision. Also on June 26, diplomats of England, Austria, Prussia and the Dutch Republic meet at Reichenbach to discuss possible military intervention against the French Revolution.

July 12, 1790: The Assembly adopts the final text on the status of the French clergy. Clergymen lose their special status, and are required to take an oath of allegiance to the government: Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

July 14, 1790: The Fête de la Fédération is held on the Champ de Mars in Paris to celebrate the first anniversary of the Revolution. The event is attended by Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, the National Assembly, the government, and a massive crowd. Lafayette takes a civic oath vowing to "be ever faithful to the nation, to the law, and to the king; to support with our utmost power the constitution decreed by the National Assembly, and accepted by the king." This oath is taken by his troops, as well as the king. The Fête de la Fédération is the last event to unite all the divergent factions in Paris during the Revolution.

July 23, 1790: The Pope writes a secret letter to Louis XVI, promising to condemn the Assembly's abolition of the special status of the French clergy.

July 28, 1790: The National Assembly refuses to allow Austrian troops to cross French territory to put down an uprising in Belgium — the Brabant Revolution in the Austrian Netherlands — partily inspired by the French Revolution, though actually conservative in its goals.

July 31, 1790: After Marat publishes a demand for the immediate execution of 500 to 600 aristocrats to save the Revolution, the National Assembly decides to take legal action against Marat and Camille Desmoulins because of their calls for such revolutionary violence.

September 4, 1790: The once wildy popular finance minister Necker is dismissed. The National Assembly takes over management of the public treasury.

October 6, 1790: Louis XVI writes his cousin, Charles IV of Spain, to express his hostility to the new status of the French clergy.

October 21, 1790: The National Assembly decrees that the tricolor of red, white, and blue will replace the white flag and fleur-de-lys of the French monarchy as emblem of France.

November 4-25, 1790: Insurrection in the French colony of Isle de France (now Mauritius) begins on November 4, followed weeks later by the uprising of black slaves, on November 25, in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti).

November 27, 1790: The National Assembly decrees that all members of the clergy must take an oath to the Nation, the Law and the King. A large majority of French clergymen refuse to take the oath.

December 3, 1790: Louis XVI writes to King Frederick William II of Prussia asking for a military intervention by European monarchs to restore his authority.

1791: Moderates, Deadlock, and Failed Flight of the Royal Family

January 1, 1790: Mirabeau is elected President of the Assembly.

January 3, 1789: Priests are ordered to take an oath to the Nation within twenty-four hours. A majority of clerical members of the Assembly refuse to take the oath.

February 24, 1791: Constitutional bishops, who have taken an oath to the State, replace the former Church hierarchy.

February 28, 1791: The so-called Day of Daggers takes place, in which Lafayette orders the arrest of 400 armed aristocrats who have gathered at the Tuileries Palace to protect the royal family. They are freed on March 13.

March 2, 1791: Abolition of the traditional trade guilds, one of many Old Regime corporative bodies the Revolution will eliminate.

March 10-25, 1791: Pope Pius VI condemns the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and on March 25, diplomatic relations break between France and the Vatican.

June 20-21, 1791: The infamous Flight to Varennes takes place. In the night of June 20-21, Louis XVI, the Marie-Antoinette, and their children abscond from the Tuileries Palace and flee by carriage in the direction of Montmédy. Unfortunately for them, they are spotted and recognized in the town of Varennes by a postman.

July 16, 1791: The formation of the Feuillants Club (offically called "The Society of the Friends of the Constitution"). This political club came into existence because the National Assembly was diverging, with moderates on the right, who wanted to preserve the position of the king and supported the creation of a constitutional monarchy, along British lines; and the radical Jacobins on the left, who wanted to push for a democratic republic and the overthrow of Louis XVI. The Feuillant deputies emerged when they publicly split with the Jacobins, on July 16, over the latter's plan for a popular demonstration against Louis XVI to take place on the Champ de Mars the following day.

August 21, 1791: The Haitian Revolution begins on the night of August 21, 1791, when the slaves of the French colony of Saint-Domingue rise in revolt, with thousands of slaves attending an underground vodou ceremony and proceeding to kill their masters, plunging the colony into civil war. Soon, the Haitian slaves take control of the entire Northern Province, while whites kept control of only a few isolated, fortified camps.

1792: The Revolution Goes to War and Overthrows the Monarchy

[The French National Guard joins the army for war in September 1792 against the First Coalition]

January 23, 1792: The slave uprising in Saint-Domingue — part of the Haitian Revolution — causes severe shortages of sugar and coffee in Paris, leading to riots against food shortages and the looting of many food shopsin Paris.

February 7-19, 1792: Treaty of Berlin is made between Prussia and Austria, a defensive alliance, against Poland (which was being dismantled in the Partitions of Poland, not to mention the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth drafted their own highly liberal constitution) and revolutionary France. Treaty is ratified on February 19. This sets the stage for the eventual invasion of France by Austrian and Prussian forces.

March 10-23, 1792: Brissot gives a speech attacking Minister Lessart (a minor nobleman who supported reforms but not full-blown revolution) because of his opposition to war against the conservative and interventionist monarchies of Austria and Prussia. He is impeached for his pacifism by the Girodin faction on March 10. The Feuillant ministers resign in his wake. Dumouriez gets appointed to Foreign Affairs on March 15 (and later becomes a general). Later, on March 23, a Brissotin government is formed with Étienne Clavière in the Finance Ministry and Roland as Minister of the Interior.

March 24-April 4, 1792: A decree recognizing the political rights of free men of color and free blacks is put forth on March 24, and later ratified by Louis XVI on April 4. The next day, France delivers an ultimatum to Francis II, king of Bohemia and Hungary — aka the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor — to disperse the gatherings of emigrants in the Rhineland, and it is rejected. On March 28, the Brissotin government passes an amnesty decree for political crimes. Meanwhile, on March 30, they pass a decree confiscating the property of nobles who had emigrated since July 1, 1789.

April 20, 1792: Beginning of the War of the First Coalition, as France declares war on the King of Bohemia and Hungary — the Austrian Habsburg Emperor Francis II. Months later, in July, the King of Prussia — Frederick William II — declares war on France under the terms of the Treaty of Berlin of February 7, 1792.